Spay/neuter timing is a controversial topic… and one that you will encounter on a regular basis in small animal practice. While pets have traditionally been spayed or neutered at 4-6 months of age, recent studies have led both the veterinary community and the general public to question that wisdom.

It is important for you to understand the issues involved in the spay/neuter timing debate, so that you can educate your clients and help them provide the best possible care for their pets.

Several studies, conducted at the University of California, Davis between 2013 and 2017, led to the recent increase in conversation about spay/neuter timing.

These studies found:

- Increased risk of hip dysplasia, cruciate ligament tears, and lymphoma in Golden Retrievers neutered at an early age(1)

- Increased risk of orthopedic disease in German Shepherds neutered at an early age(2)

- Increased risk of immune-mediated diseases in neutered dogs(3)

While these studies raise important questions, it is difficult to use them as a basis for broad generalizations. All three studies were retrospective and based on relatively small patient populations, making it difficult to prove a link between sterilization and observed outcomes.

The University of Georgia also examined the spay/neuter issue in 2013, using a much larger sample size: 70,574 dogs seen at the UGA teaching hospital between 1984 and 2004.(5) Researchers examined the age of death and cause of death for each patient in the study.

Principle findings included:

- Sterilization is associated with increased longevity in male and female dogs.

- Intact dogs are more likely to die of trauma, infectious disease, vascular disease, or degenerative disease.

- Spayed or neutered dogs are more likely to die of neoplasia (lymphoma, osteosarcoma, mast cell tumors, transitional cell carcinoma) or autoimmune disease.

Increased longevity among sterilized dogs was not only reported in the UGA study (a referral population), but also in the 2013 Banfield State of Pet Health Report (a general practice population). This report, which examined data from over 2.2 million dogs across the country, found that spayed female dogs live 23% longer than intact females and neutered male dogs live 18% longer than intact males.(6)

Although the UGA study determined that spayed and neutered dogs are more likely to die of cancer than intact dogs, it is important to remember that, on average, sterilized dogs in the study lived longer than intact dogs. Cancer incidence increases with age, therefore, we should expect cancer to play a larger role in the mortality of sterilized dogs.(4) This issue often complicates efforts to determine the effects of spay/neuter on cancer incidence; it is difficult to determine whether increased cancer rates are caused by hormonal effects or simply an effect of pets living longer.

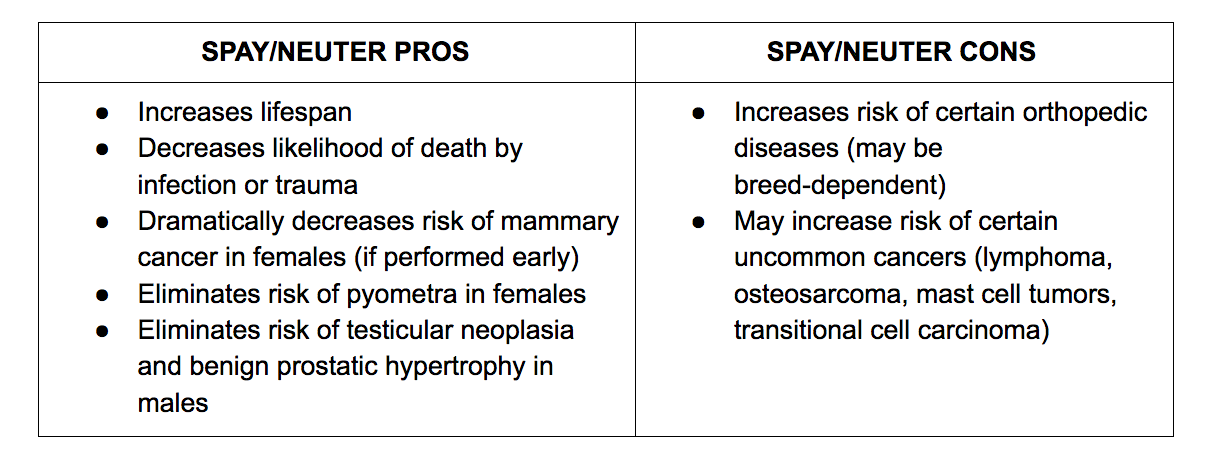

In addition to these recent findings, there are other well-known benefits of sterilization to keep in mind. Early spay (before the first heat cycle) dramatically decreases the risk of mammary cancer in females(7) and spaying at any age eliminates the risk of pyometra.(4) In males, neutering eliminates the risk of testicular neoplasia and benign prostatic hypertrophy.(4)

So, to summarize...

Note that the conditions prevented by sterilization (mammary cancer, testicular cancer, pyometra, and benign prostatic hypertrophy) are all relatively common in intact pets. The cancers thought to increase in likelihood with sterilization (lymphoma, osteosarcoma, mast cell tumors, transitional cell carcinoma) are uncommon in both intact and sterilized pets.(4)

While a client who has personal experience with one of these uncommon cancers may prefer to delay or avoid spay/neuter, pets appear to experience the greatest overall reduction in cancer risk when spayed or neutered at 4-6 months of age.(4)

The risk of orthopedic disease, however, is a more significant concern when determining sterilization timing. Studies have demonstrated an increased risk of hip dysplasia, cranial cruciate ligament tear, and other orthopedic conditions when some breeds of dogs are spayed or neutered before growth plate closure.

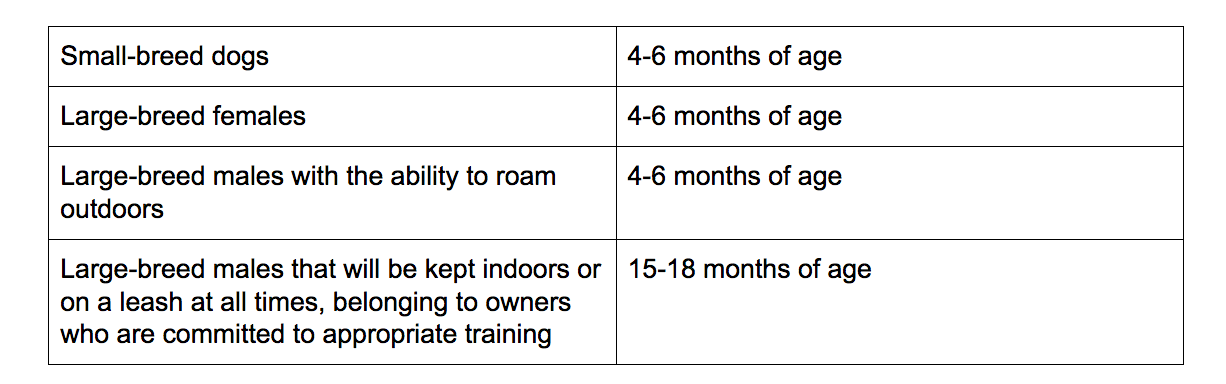

In small-breed dogs, hip dysplasia and cruciate rupture are uncommon. Therefore, small-breed dogs should be spayed or neutered at 4-6 months of age, before sexual maturity.(4)

What about large-breed dogs, who may be more susceptible to orthopedic disease? Should clients postpone their large-breed dog’s spay or neuter until after the growth plates have closed?

In a female dog, delaying spay surgery will allow the growth plates to close but will increase the dog’s risk of mammary cancer. According to the UC Davis study, a Golden Retriever spayed before one year of age has an 8% likelihood of cruciate rupture; this likelihood can be nearly eliminated by delaying her spay (although this finding was based on a small sample).(1)

In contrast, a female dog spayed before her first heat has a negligible (0.5%) risk of mammary cancer; this likelihood rises to 26% if she is spayed after her second heat cycle.(7) Protecting against orthopedic disease increases the risk of mammary cancer, and vice versa.

Given that approximately half of canine mammary tumors are malignant, however, spaying large-breed females at 4-6 months of age remains an optimal choice in most cases.(4)

The benefits of neutering male dogs, however, are not as age-dependent as the benefits of spaying females. Delayed neutering of large-breed males, at 15-18 months of age, can decrease the risk of orthopedic disease while still providing medical benefits.

Clients who choose to delay neutering must understand, however, that their dog will require constant confinement or restraint (to prevent roaming, injuries, and contributions to pet overpopulation), may require additional training (due to increased likelihood of territorial aggression), and is more likely to urine-mark. In the right home with the right owner, however, there is a strong argument to be made for delayed neutering of large-breed males.(4)

As much as we would like to have a single “right” answer to the question of optimal spay/neuter timing in dogs, there is no such thing.

In general, however, the following guidelines can be considered as a starting point:

Discuss spay/neuter timing with dog owners at their puppy wellness visits, modifying your recommendations as new research becomes available. If a client elects to delay their dog’s spay or neuter, discuss the risks and benefits of doing so and allow them to make an informed decision.

Resources:

- Torres de la Riva G, Hart BL, Farver TB, et al. Neutering dogs: effects on joint disorders and cancers in golden retrievers. PLoS One. 2013;8(2).

- Hart BL, Hart LA, Thigpen AP, Willits NH. Neutering of German Shepherd Dogs: associated joint disorders, cancers and urinary incontinence. Vet Med Sci. 2016:1-9. doi:10.1002/vms3.34. 4.

- Sundburg CR, Belanger JM, Bannasch DL, et al. Gonadectomy effects on the risk of immune disorders in the dog: a retrospective study. BMC Vet Res. 2016;12(1):278. doi:10.1186/ s12917-016-0911-5.

- Bushby P. The Optimal Age for Spay/Neuter: A Critical Analysis of Spay Neuter Literature.

- Hoffman JM, Creevy KE, Promislow DE. Reproductive capability is associated with lifespan and cause of death in companion dogs. PLoS One. 2013;(8(4)).

- Banfield. State of Pet Health Report.

- ACVS. Mammary Tumors.